In the late ’90s, when I was too young to care about girls but old enough to want to prove my manliness, my Papa Larry asked a simple favor.

Help me dig a hole.

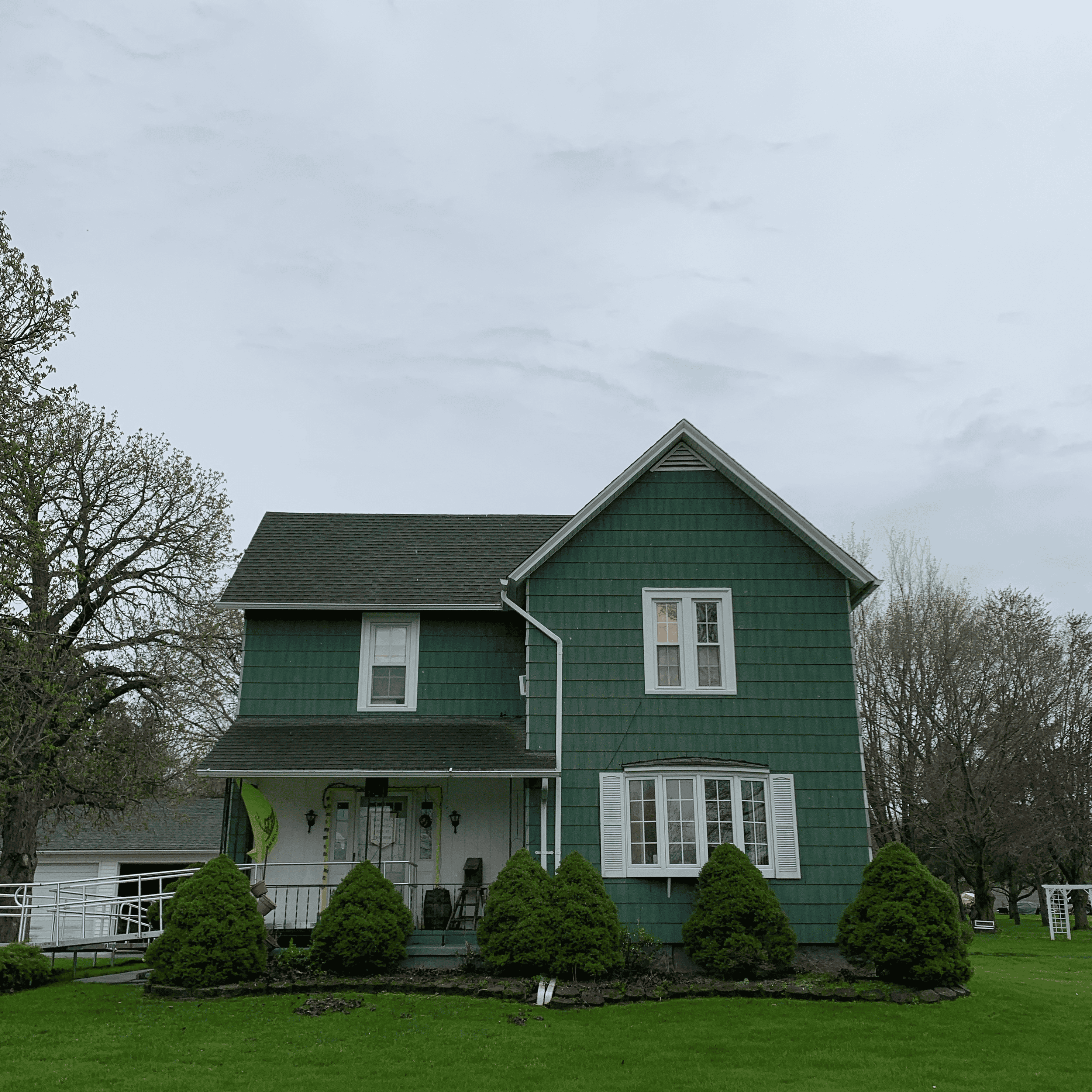

My grandparents lived on a little plot of land on Humphrey Road that danced in my daydreams as my own Garden of Eden. It seemed a vast expanse at the time. A dark green house, a three-car garage and a pair of sheds nestled on a fertile property where the best food grew, the greatest adventures began and where I felt utterly safe, kept so by my grandparents’ love.

On the east side, a border of lilac bushes, a scent so thick in the spring I could taste it in my throat. A prosperous apple tree abutted them, paired with a shrub that produced fiery orange berries. A whisper of a ditch separated the property from the neighbors, where a trio of ashen pups was born outside a doghouse one summer.

On the west side, evergreens that provided excellent cover for forts — their branches sagging too low for adults to crawl under but just high enough for me — and a smooth-barked maple tree that was my favorite for climbing. Cherry trees grew out front and out back; bitter, tart fruits that I sampled and spat out.

On the far reaches of the property was a bonfire pit, circled by boulders. I wondered at how those stones charred, cracked and split from the heat of the flames. I didn’t think anything could hurt rocks. One summer, just a few feet away, my grandparents set up a big tent from the attic for my brother and me to use as a fort. It was plain, empty, and smelled of mildew and vinyl — a paradise within a paradise.

In the summer, killdeer roamed the far front yard, shrieking as they tried to lure us away from their ground nests. I thought they were silly birds and loved letting them think they were winning. Then I’d run away to wonder at the multicolored pebbles from various travels saved in the footprint of the old pump shed, or sidle between the house and the hedgerow to turn on the hose and run through its water, or tiptoe over the big rocks circling the flagpole.

On that summer morning, Papa Larry threw down the shovels just in front of the gazebo.

Like most boys my age who roamed the countryside, I’d dug plenty of holes. Whenever I made the mistake of announcing I was bored, someone handed me a shovel and told me to dig until I found something. And find things I did — marbles, plasticky pool fragments, old bits of ornate pottery, black rocks that I was convinced I could sell to a coal company, and the occasional horseshoe.

But this was a different kind of hole. It had to be as wide as me lying down and as deep as my little brother standing up. It had to hold enough water for a dozen goldfish and some aquatic plants.

I wanted to impress Papa Larry — and besides, my emerging adulthood was on the line. So I dug like I’d never dug before.

After five minutes, I was beat. After ten, I was convinced we had to be close to done. After twenty, I despaired at how far away we still were.

Each wheelbarrow load of dank, black topsoil was followed by another, and another, and another.

I don’t remember finishing the hole that day. I’m sure I gave up, went home, and left my grandpa — an unflinching vision of masculinity in my young mind — to complete the work. The next time I visited, the hole had become a pond, complete with a fountain, lily pads, and bright orange fish that rose to the surface when we approached.

That summer, that house, that land — they were an idyll. My Shire. My Green Gable. My Pemberly.

That was a quarter century ago. Ten years after we dug the hole, my grandpa was lowered into one of his own. Grandma Evelyn kept up as best she could but, as it does, time crept in to the property. Its expanse hastened when she followed my grandpa to death. My parents and uncle are diligent caretakers but have plenty else to worry about.

Two summers ago, I pulled the rocks from around the flagpole and threw them into that hole. Its liner was cracked and leaky; it hadn’t held fish for years. It would be a safety hazard during my brother’s upcoming wedding.

With the job done, my mom left me alone for a moment. I stood quietly, staring at the work we’d done — and that I’d undone. My mom felt energized by the improvements she and I had made to get the yard wedding-ready: a cleaned, freshly painted arbor in a new spot; pressure-washed pavement and walls; dead trees felled and old stumps hidden.

But all I could see was what used to be, and the quiet absence of my grandparents. It felt less like revitalization and more like managed decline. I wiped my tears and sweat into my sleeve and turned to take in the view — a painful tradition I’d begun years ago during my brief returns from my home in Florida.

I wondered what other small insults time would bring: which tree might fall next, which handcrafted project might start leaking, which rocks might crack and shift — chipping away at whatever youthful beliefs in permanence I still held.

That was then. But in September, I returned to Eden — this time with a vision for the future.

I’ve started cutting down the trees that have grown brittle and dangerous with age, making room for new growth. In time, I’ll harvest the apples and cherries, planting companions to encourage their fruiting.

I’ll place fresh rocks for my own young son to tiptoe across, grow hedges for us to sidle around, and sit with him in the footprint of the old pump house, where we’ll admire shiny stones together and add a few of our own.

Someday, maybe, my son and I will dig a hole, filling it with fish that rise to the surface when we approach. My parents, now his grandparents, will watch as he begins to explore the land that shaped me.

And in that moment, the circle will come full. Life will bloom again on this little plot of land on Humphrey Road, carrying the best of the past forward.