The older I get, the less sure I am of anything. Many of my past convictions are somewhere back along the roadside, gathering dust and cobwebs. Others are repurposed, refined, different than before. Some things I once mistook for wisdom were really just certainty calcified around ignorance.

I find myself softening — not only in my midsection — becoming more curious, more forgiving of imperfection, more willing to taste what I once turned away from. The child inside me is full of wonder, and I ache for his unguarded appetite.

My real child — the one living in my home, not the metaphorical one inside me somewhere — likes apples, but doesn’t love them. He prefers them cored and peeled but left whole, to carry around and munch on — until he forgets about it and the dog finds it.

I didn’t love apples, either. Not really. I certainly ate them. I’m not sure I was aware of the many different varieties. Somewhere around the time I started to lose my baby teeth, I stopped trusting apples. Their sharp crunch felt like too much risk for too little sweetness. But somewhere along the way, I learned to notice the things I once overlooked.

In “North Woods,” one of my favorite novels, colonist Charles Osgood is fighting on the side of the Redcoats when he’s stabbed in the chest by a French soldier. He writes that the blade “passed between my ribs and gently kissed my heart.” In his convalescence, he finds that he is stricken with pomomania — an obsessive preoccupation with apples.

He wonders how that came to be: “A kiss somewhere, on someone’s lips still wet with cider? The serpent that tempts us all? Or was it simply this: that the French soldier I surprised behind his bulwark on that fatal day upon the Plains of Abraham was slicing a sweet pippin with his bayonet when he rose and thrust it into my chest?”

Nobody stabbed me in the chest. Not literally, at least. Rather, I suspect I came to my growing love of apples, verging on pomomania, by the ripening of age.

Here’s the part where I should admit that I grew up in an apple orchard. Sort of. My paternal grandparents once shared a property line with Newroyal Orchards, holder of acres and acres of dwarf apple trees.

Some days the air behind the house was heavy with the ferment of fallen apples; other days it was sharp with a chemical tang, like rainwater on pennies. You could hear the sprayers before you saw them — a long, rising blare, like a five-alarm fire horn tearing through the rows. People think I’m joking when I tell them I used to run through the pesticide mist like a Cessna cutting through clouds.

At some point, the town used eminent domain to seize the back half of my grandparents’ property and cut us off from the orchard. The new road they built had a steep incline, a blind corner and two deep ditches, all of which did a good job of keeping us away from the orchard. That’s OK. Those apples tasted miserable and had the texture of oatmeal. We called them horse apples.

As I fell deeper into my relationship with saison and farmhouse beers at Green Bench, my pals behind the bar — James and David especially — pushed me to try the cider options. My experience with cider at that point, aside from the nonalcoholic jugs I slugged down every fall, was with Woodchuck and some sticky-sweet blackberry grog from Becker Farms in Gasport. Cider made me think of rough headaches and rougher mornings. I resisted until one day I decided it was time.

It was a slow afternoon in the Florida winter. I was sitting at the bar in the old brewery space, late sunlight slanting through the massive open windows. Maybe it was desperation — I’d had everything on that day’s menu dozens of times — but I ordered a glass and took a slow sip.

Imagine my surprise when I found that cider could be dry, nuanced, alive with flavors my adventurous tongue had never met. Bittersweet? Bitter sharp? Malolactic fermentation? It was as if someone had peeled back a thin veneer and revealed a world that had been there all along.

And though I was surprised by this revelation, I wasn’t startled. It’s just part of the softening of age.

A few weeks ago, buried in an email from McCollum Orchards, the place in Lockport where we cut our own fresh flowers, my eyes lingered on a note.

We’re excited to share that our no-spray Northern Spy apples are available this season! We are offering an 10lb box for $15 each. These crisp, flavorful heirloom apples are perfect for apple pie baking, sauce-making, or enjoying fresh. As the saying goes, ‘Spies for your Pies.’

Two weeks later, I had 10 pounds of handsome apples — freckled, uneven in size, some bruised or brown-spotted.

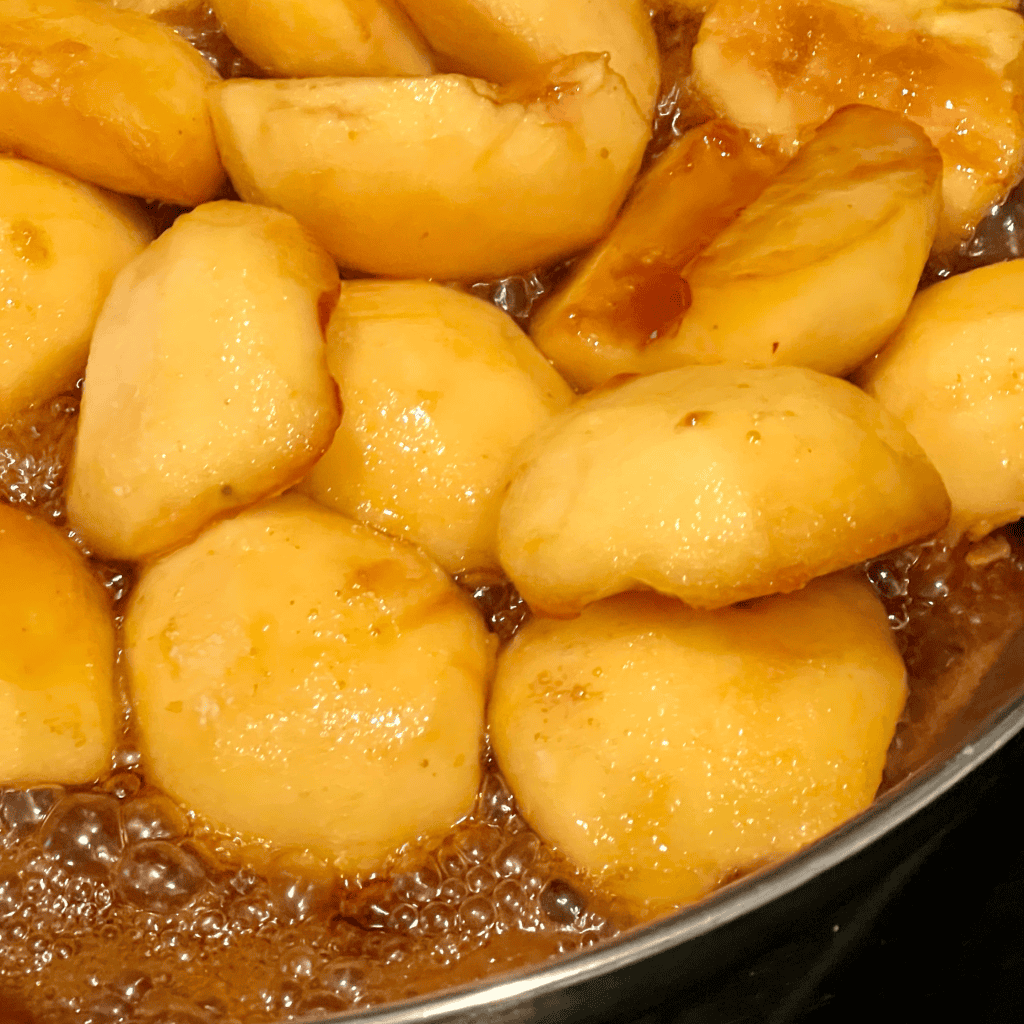

I cut them into thirds, smothered them in butter and sugar and baked them into a tatin (recipe via Smitten Kitchen). The kitchen filled with the smell of butter darkening toward toffee. My mom and son lingered by the stove beside me. Through the oven window, the puff pastry rose and browned while the syrup bubbled and the apples slumped gently into each other below.

In the world of beautiful apple pastries, the tatin is among the homeliest. But as the fruit caramelizes and collapses, it becomes beautiful in its own way.