A thin strip of snow lingered in the shade of the garage on the afternoon when spring first teased its emergence. It called me to turn to the work at hand: trees to cut, saplings to plant, soil to turn. Work that asked everything of my body and left no space for thought.

That morning we had chased the sun to Niagara Falls, but drizzle sent us home early. I headed to Gasport instead.

My first job was to take down a pair of ornamental plums along the driveway. They were ungainly, ugly things. Still, I couldn’t shake the thought that my grandparents had once set them in the ground. I pictured Larry and Evelyn pressing soil into place, the same way they once tucked me beneath blankets — a thought sharpened by the fact that it had only been a month since my dad’s sudden death. As I drove the chainsaw through the trunk, I struggled to focus. I sent a video of the work to my brother, fishing for amnesty. “Modern day lumberjack Ren,” he wrote back. “Grandma Oven hated that tree lol.”

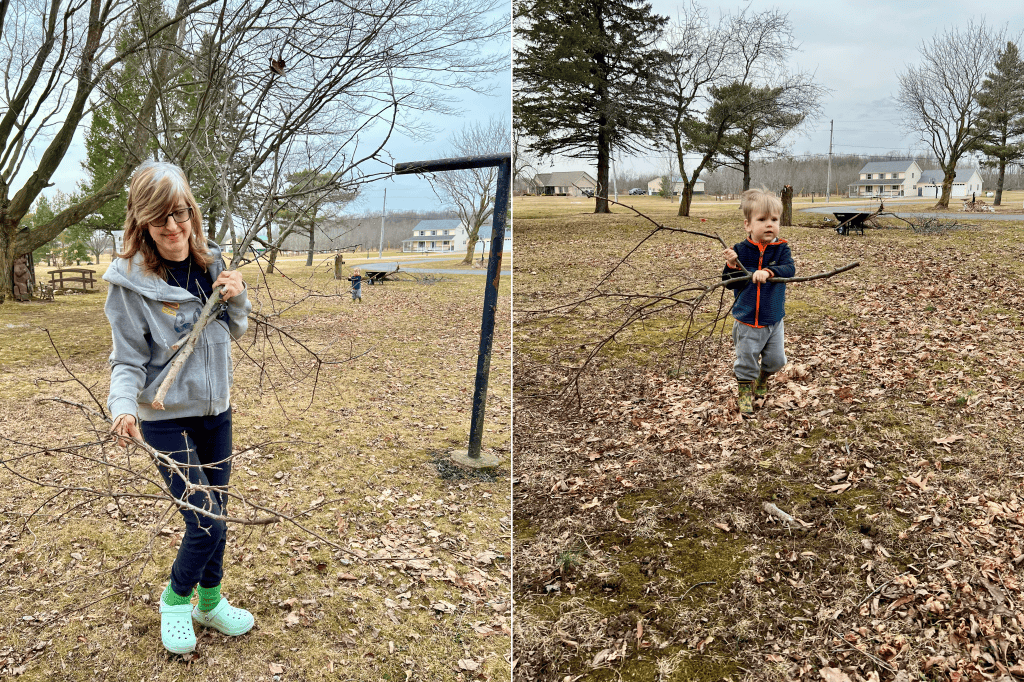

That helped. Enough to keep going. The trunk split, the canopy dropped, and I just stared. My mom moved beside me and gave words to my shock: They look bigger when they’re on the ground, don’t they? They sure did. Then came the grind.

Cut, drag, throw.

Cut, drag, throw.

Cut … fix the damn chainsaw.

Cut, drag, throw.

The muddy lawn and the flat tire on my mom’s old wheelbarrow slowed the work. So did my spent muscles, and the extra weight I carried. I sweated through the thaw in the company of robins and silence.

As the hours passed, two realizations set in: This was harder than I expected, and I’d need to lower my expectations for how much I could do in a day. Limbs and chunks of trunk seemed to queue for my removal. The pile seemed to swell instead of shrink. Another ornamental plum stood close by, daring me.

I was ready to quit when I caught sight of my mom and Augie dragging limbs behind me. I stopped. For a moment I just watched. A swell of love steadied me and eased the weight in my arms. I bent again to the work.

By sunset, the first plum tree was gone, just an 18-inch circle trimmed flush with the lawn. The air had neared 70, but the snow in the garage shade held fast, as if it might never leave.

My goal was to prepare for the half dozen apple saplings I had ordered nearly a year earlier from a nursery in Ithaca. I had gotten it in my head that if beer could reflect time and place, then cider could go even further. Apples were something I could plant, tend and someday ferment on my family’s land. The thought stayed with me, like the blights I’d soon learn about.

Most of life’s valuable lessons come hard. I revisited one of them as I sketched out my orchard: Make a plan and take action, but leave room for chance.

One hot spring night in St. Petersburg, months before most people knew I’d be moving back to Buffalo after nearly a decade and a half in Florida, I had opened the website of Cummins Nursery, one of the country’s leading suppliers of heirloom apple trees. My plan was to pick a handful of trees to plant in my parents’ yard, ones that could someday yield complex ciders without too much fuss, since I’d be living 40 minutes away.

After a few minutes scrolling, I realized I was out of my depth. Beyond flavor and blending potential, there were pests, dieases, soil preferences, and — most important — bloom groups. I needed varieties that would flower together so insects and the wind could do their work and ensure fruit would follow.

My spreadsheet filled with notes and colors. The more I typed, the less control I seemed to have. So I gave up control. I gathered the names of apples known for reliable cider and manageable upkeep, closed my eyes and picked Dabinett: An English apple described as “small and yellow-green flecked red, with flesh that is tinged green. It yields a bittersweet juice that is astringent and high in fruity tannins. A vintage-quality juice.”

From there, I needed companions. I picked Harrison, a New Jersey native, nearly lost to Prohibition, known for its dark, rich juice with a balance of tannin, sugar and acid. Good for blending, good on its own.

That left me on a limb. Two apples that might taste good together, but wouldn’t grow well together. Neither was from New York. And neither was the kind you’d pluck off a branch for a snack in the fall.

That’s when I added Liberty, a relatively uncelebrated New York apple. Not flashy. Sturdy. Good for cider, good for eating, good for pollinating.

I spent my last months in Florida sketching where to put the trees and what they’d need to thrive. They became my characters. They became my friends.

Dabinett: the serious one, vintage quality, an anchor.

Harrison: nearly lost, resurrected; a tree with a story.

Liberty: pragmatic, local, steady.

At times, it felt like nothing was happening during those months. But in hindsight, it was its own season: numbers, notes and imagined orchards, roots taking hold in the dark where no one could see.

Once the plum trees were down, the next few weeks brought little progress. Bad weather, surprise visits from friends and head colds from Augie’s day care kept me away from the house. I only had one day a week to work there, so each delay felt heavy.

Still, life went on. Friends had babies. My son tried the potty for the first time. Aunts and uncles took turns at the hospital with my grandmother. All the while, the cold dragged, blunting the welcome I wanted to give my saplings.

We left Florida to be closer to family, but I still felt adrift in New York. The weather was harsh, the distractions constant. Nothing matched my vision. I was still haunted by an idea I believed I’d beaten: that it was the place that needed to change, when really it was me.

The last weekend before we were due in Ithaca, I felt the pinch. I had mapped out spots for the trees but needed soil, fencing, wire mesh, posts. I had holes to dig, stakes to drive, chores stacked high. Then Keeley’s brother flew in for a visit. Lunch with family or hours of work? A few months earlier I might’ve chosen the work. This time I chose lunch and I tried not to think about it. Maybe I was relieved.

Afterward, I spray-painted some X’s on the lawn to mark out another day’s work, then packed it in.

Gardeners have a phrase about growth. They say trees sleep, then creep, then leap. In that moment, I felt firmly in the creeping stage: slow, unsteady, but inching forward all the same.

We left for Ithaca on a chilly Saturday morning, rain flicking against the windshield as we sped down the 90. Though we were going to pick up my trees, it was also meant to be a little family trip: cider stops for me and Keeley, the Sciencenter for Augie, a waterfall detour for all of us. But my mind kept drifting.

I felt uneasy about ruining the yard.

I had already poured in too much money. The saplings, posts, fencing, chainsaw, all of it.

I had spent months talking about apple trees, sketching plans, building spreadsheets. It felt like my reputation was tied up in them, maybe even my sense of self. What if I botched the planting and killed them before they ever had a chance?

And beneath that was something harder to name. The fear that I was moving on too soon. Tearing up memories I still wanted close.

So while we sipped cider and watched Augie run from exhibit to exhibit, I couldn’t quite relent. The trip was lighthearted, but underneath I carried the weight of those six little trees waiting at the nursery, as if I were moving forward with the wrong work at the wrong time.

Sunday morning finally led us to Cummins. The parking lot was empty, just gravel along a busy road. I left Keeley and Augie in the car and stepped through an unlocked door into near-darkness. Only a sliver of light cut through the covered windows. Bundles of saplings leaned against the walls, tagged by last name. Some were massive, some just a tree or two. Mine — six young trunks bound together — waited on the far side of the room. I whispered hello as I touched them for the first time. Back in the daylight, I snapped a picture, then slid them into the back of the SUV. Their spindly branches reached toward Augie as we drove on to my mom’s place.

Days earlier, I had told Keeley the planting wouldn’t take more than an hour or two. Instead, we drove posts, covered roots with soil, rigged fencing and hauled water for nearly six hours in a chill that cut through the gloves. Our clothes were soaked with rain and mud; our hands went pruny from the cold. Keeley hardly complained. I was still reeling from losing my dad, unmoored in ways I struggled to admit out loud. And there she was, steadying me just by working beside me. It was enough to make me feel, again, that I hadn’t lost my whole world.

As we wrapped the fencing around the last tree, the cold began to clear and we felt a warm breeze. It carried more than physical relief. It felt like a promise of seasons still to come.

Have you ever stood on the edge of a continent? On a vacation this summer in Dorset, looking up at the cliffs and out at the English Channel, I felt it again: a sensation that rises in the chest, dizzying, as if the body remembers that someone before you looked at this same horizon and crossed it.

It isn’t fear of falling. It’s the weight of knowing someone once stood here and decided to go on. Small, but not meaningless. Call it ancestral vertigo.

I’ve felt it at Moher in Ireland, on the California coast — places where land runs out and the sea dares you forward. My dad kept his own decadeslong vigil on a different cliff, dreading the end of his life, a line of Ojibwe and Europeans stretching behind him, improbably leading to me.

Standing there, reflecting, it feels as if an invisible gardener has been at work all along, tending roots we didn’t know were there, coaxing them toward light. I don’t believe it. And yet, the odds that I’m standing here at all leave me reeling.

What cliff awaits my trees, some of which will surely outlive me? Abundance? Glory? Blight?

Or just the quiet work of roots and hands, mud on boots and gloves soaked through, steadying us against the vertigo?

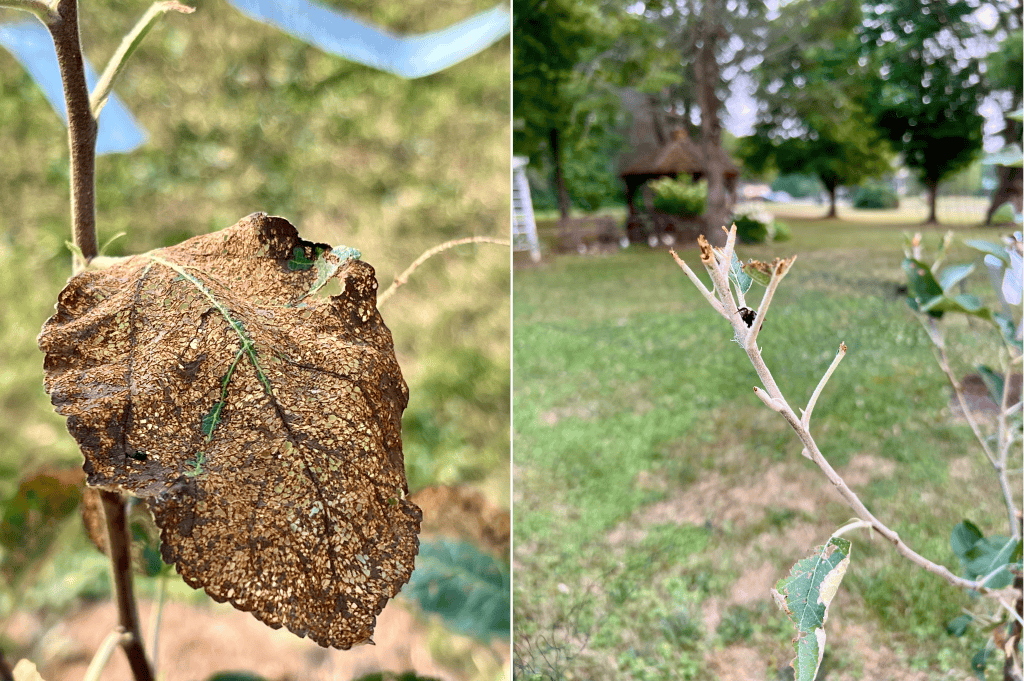

In late spring, I noticed one of my anchor trees — a Dabinett — had been girdled. A clean circle carved at the base, maybe by a rodent, maybe by my uncle’s weedwacker. I taped it, set a guard around the trunk and started watering on the double, hoping it would pull through.

Not long after, I realized the 10-20-10 fertilizer Cummins recommends isn’t strictly organic. The trees loved it, but so much for my first shot at homegrown organics. I’d have to wait three years to claim it now.

Then came the bugs. Andrew spotted the aphids at my dad’s memorial party. I watched ants carry them up to the youngest leaves, like farmers planting crops, and ladybugs arrive to feast. Too few of them. Neem oil became my summer companion. Then Japanese beetles found the trees, chewing leaves into lace. Their shiny backs gave them away. I shook them into buckets of soapy water, again and again, but they always came back.

Deer took a turn too, stripping the midsection of two saplings clean. Before I left for a vacation, I armed my mom with sprays, whistles and Irish Spring hung in pantyhose. The deer didn’t return.

By late summer, I gave up on the wounded Dabinett. Its leaves blew away and its trunk browned and hardened, lifeless. But the other five trees thrived. The Harrisons shot up past eight feet, the Liberties already formed their bell shape, and the second Dabinett was trouble-free.

Becoming a parent has made me alert and protective, and that has carried over to the orchard. I caught myself watching for more intruders, pacing the perimeter, fretting over drainage and heat. At first, the rain was too much, pooling around the bases of the trees planted in clay-heavy soil. Later, it was too little, and the ground cracked. My uncle stepped in to water. Every stage felt like a new test. Nature does what it wants, but I was still out there, tugging, coaxing, tending.

In hope, I ordered five more trees for next season: Wickson Crab, GoldRush, Ashmead’s Kernel and another Dabinett. New roots for the years ahead.

Wickson: bringer of fire, a tiny fruit packed with sugar and acid, sparking life into any cider blend.

GoldRush: the steady one, generous and reliable, its fruit sweetening with storage.

Ashmead’s Kernel: the oddball, russeted and complex, a taste that doesn’t show itself all at once but lingers and unfolds.

And a new Dabinett: a replacement, but not a repeat. It will have its own story to tell.

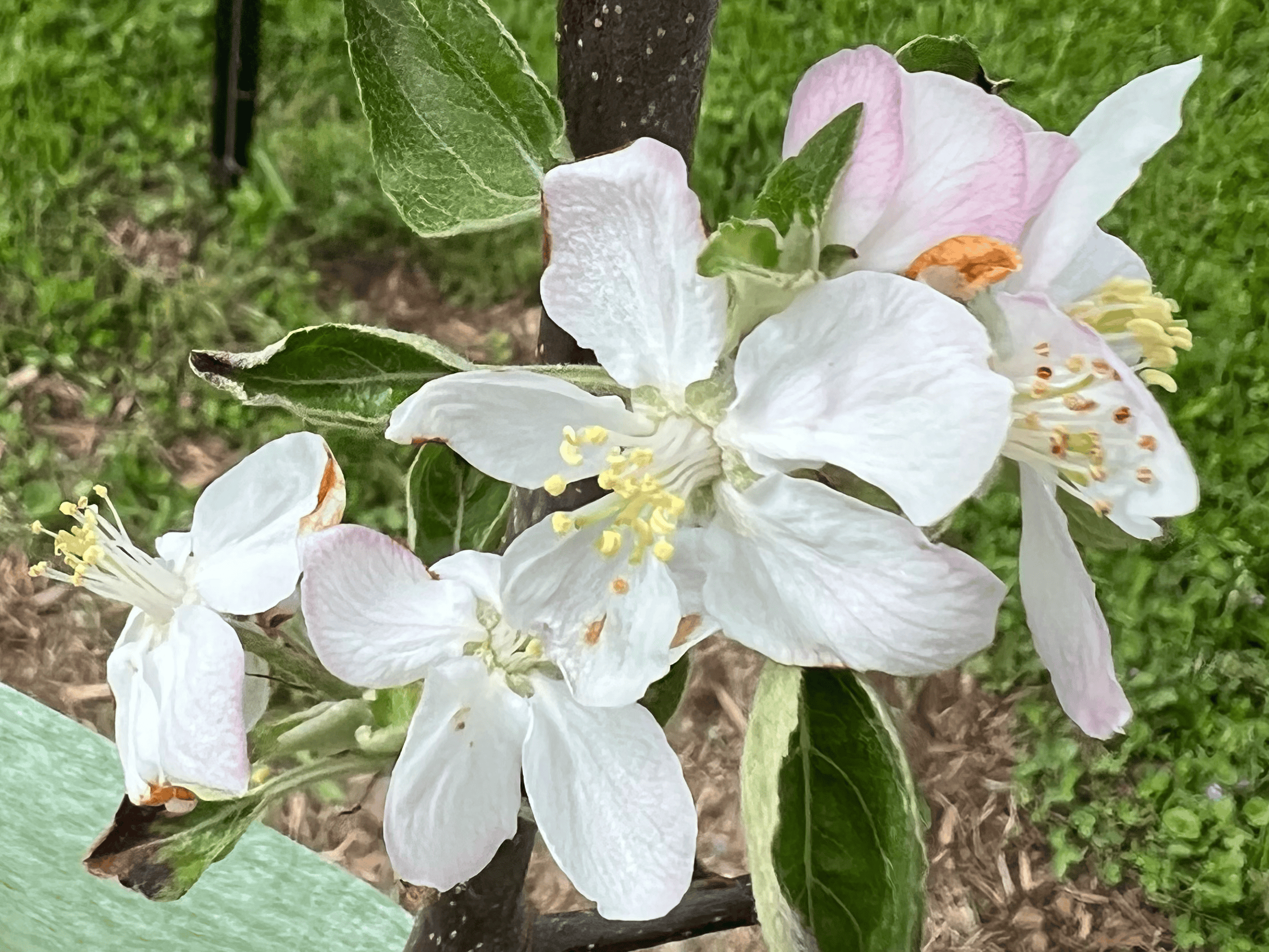

The trees did what they were supposed to do this first year. They slept. Most of their work happened out of sight, roots pushing deeper into the clay-rich soil, anchoring themselves against the seasons to come. But they weren’t entirely still. They sent up new shoots, stretched out branches and put out leaves enough to show they were on their way.

I can’t say the same for myself. I had grand plans. Too many, if I’m honest. A pergola that sat boxed until September. Walls never painted. Wood still unsplit. Most of the projects never left the page.

Still, the yard felt steadier, the trees more rooted, and me alongside them.

By September, the air had suddenly turned sharp and cool, and change began popping up everywhere, even the breakfast table. While he was pondering a strawberry, Augie looked me in the eyes and asked:

Where’s your daddy, daddy?

I caught my breath. I had been waiting for this moment for half a year, but could barely summon a response.

That depends on your belief system, buddy.

I told him I’d like to think he’s a bird flying around our heads or, better yet, the wind that blows when we’re all alone.

He stared without words, then hopped down to the bathroom. The kitchen went quiet. Such a small thing, but it felt like the floor had shifted under me.

The birds and the wind. Some call that God. I call it Grandma Evelyn. Jamie. Mo. Papa Larry. Dardenne. Nick. Jonah.

And, yes, my old man.

A few weeks later, as I meandered through the lawn, admiring the summer’s work, a light wind shook the leaves on my young apple trees. I looked up for a moment, then down, beneath the reaching branches where the roots worked unseen, and there was only the dizzying weight of absence.